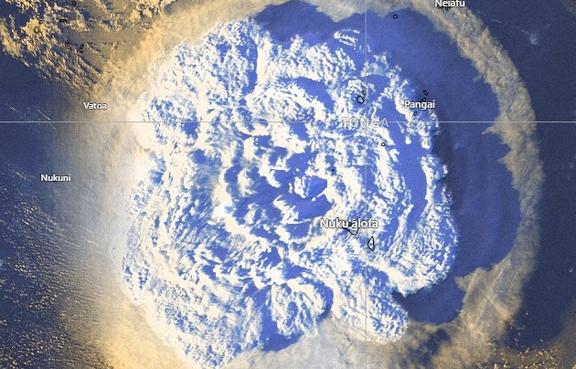

A view over an area of Tonga that shows the heavy ash fall from the eruption of Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai. Photo: Supplied / NZ Defence Force

Four months on from the violent explosion of Tonga’s Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano, scientists are still piecing together what caused the biggest eruption the world has seen in decades.

January’s blast sent shockwaves around the world: the sonic booms could be heard as far away as New Zealand and Alaska; tsunami waves radiated across the Pacific Ocean.

University of Auckland volcanologist Professor Shane Cronin was at home in Auckland when he got word of the eruption.

“I rushed back to my home office and opened up all the files, looked for all of the information I could find, and it looked like a very big eruption,” he says.

“Then all of a sudden all the links to Tonga broke down, so I had no local information, just what we were getting through in terms of some of the satellite information about the size of the event.”

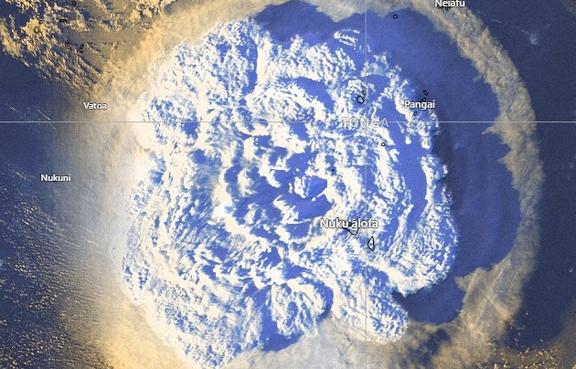

Satellite image of the eruption on January 15. Photo: Tonga Meteorological Services / EyePress via AFP

Cronin stayed up most of the night tracking the data that was available and talking to other experts.

“There were so many questions about what was going on and that volcano – I knew the volcano very well, so it was something like two o’clock in the morning I was busy beavering away writing the first article on what was going on in Hunga.”

Cronin’s work has taken him across the Pacific and Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai is one of several volcanoes he’s studied over the years.

Given the immense size of the eruption, volcanologists were focused on working out what exactly caused it.

“We really needed a mechanism that produced this large explosion, not all that much ash as far as we could tell and we needed this highly explosive mechanism to be happening extremely quickly,” Cronin says.

But getting huge amounts of magma to mix with sea water to create such a massive eruption isn’t easy.

“Our first theory which we carried on holding on to for a couple of months was that there was a collapse of the sides of the volcano, like the Mount Saint Helen’s style collapse,” Cronin says.

“That mechanism would allow deep magma buried below rock to be suddenly exposed to the ocean and so then you’d have a very large explosion.”

Professor Shane Cronin Photo: Supplied/ University of Auckland

But once Cronin arrived in Tonga and got out on a boat to survey the volcano, that theory went out the window.

The rim around the top of the crater appeared intact, so there hadn’t been a collapse of the sides of the volcano, as they’d thought.

Instead, what Cronin discovered was that the middle of the volcano’s caldera – the large depression formed when a volcano erupts and collapses – was far, far deeper than expected.

“The middle of the caldera was previously about 140, 150 metres deep and we were measuring depths well over 850 metres and going off the range of the sonar,” he says.

The eruption began fairly normally, but Cronin says something happened to turbocharge it.

“What’s happening is because there’s magma erupting out the top, the shallow part of the volcano starts to collapse in on itself – this is this caldera process beginning to work.

“The lid, or the top of this caldera starts to fracture as it’s collapsing down … this fracturing allows the sea water to get in. We’ve already brought up that magma from 5km depth suddenly to the shallow depth and we’re dropping water in on top of it.

“We’ve got the perfect conditions for our very large explosion.”

Cronin says it’s a fairly unique set of circumstances – and all of these complex processes happened fairly quickly, within about half an hour of the beginning of the eruption.

The devastating tsunami that followed in the eruption’s wake has prompted a complete rethink of the science about how underwater volcanoes can cause tsunami.

While in Tonga, Cronin has also been helping with tsunami surveying, which will help inform new risk and hazard models across the Pacific.

Source: RNZ